A Brilliant Reliever in a Brilliant Time for New York

Baseball

By TIM MARCHMAN

January 9, 2008

Reliever Rich ‘Goose’ Gossage, who pitched for the Yankees for six seasons, was elected to the Hall of Fame yesterday.

New York was brilliant in the late 1970s and 1980s. Books have been written and movies have been made about the blackouts, riots, and serial killers that haunted New York, but rarely since has the city seen such torrential creative energy. When Goose Gossage pitched his first game for the Yankees, the only place to hear hip hop was at Bronx parties where DJs ran sound systems powered by electricity from lamp posts; the year after he left, Queens' Run D.M.C. went gold. In Manhattan, artists and real estate speculators transformed SoHo, Martin Scorcese filmed his best movies, and Wall Street redefined the nature of finance. And a vicious tabloid war was on.

They were exciting times, and the Yankees were worthy of them. In the six years Gossage spent in the Bronx, the team went through 12 managers and won three pennants, two division titles, and a World Series. Again, books and movies have been created about those teams, but until yesterday, when he was finally elected to baseball's Hall of Fame, Gossage still hadn't gotten his due. More than just a dominant closer for great teams, he embodied their volatility and vigor, and that of the city in his time. He wasn't so absurdly outsized a figure as Reggie Jackson, Billy Martin, or Thurman Munson. But he was pretty close.

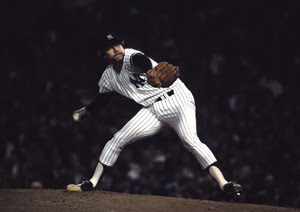

Fourteen years after his retirement, 30 years after his prime, Gossage remains the archetypal reliever. He had the violent, ferocious delivery that saw him flail his limbs and torque his whole body, driving everything he had into a fastball that hit bats like a medicine ball; he had the bizarre facial hair, which at times made it look as if Chester Arthur had taken the mound in anger, and he had the scowl of a starved and feral dog. Everything about him was scary; to this day, teams still run imitators of him out to the mound.

During his time in the Bronx, Gossage's earned run average was 2.10, and it was there that he earned his reputation. He had great seasons with Bill Veeck's Chicago White Sox, a pennant-winning San Diego team, and with Willie Stargell's Pirates, but history will remember him as Martin's fire-eating pitbull.

The skeptical baseball fan should remember, though, that just like other products of his time from Theoretical Girls to Bret Easton Ellis, Gossage's image was quite contrived at the time and has grown more so since. Gossage is recalled, for instance, as a true iron man, last and brightest of a generation of nervy warriors who shouldered workloads in relief that would break today's pitchers. The way he was used with the Yankees — he was brought in whenever the game was on the line, rather than being reserved for late-inning leads, and he would pitch up to five innings at a time — is held up by many as an ideal. (It's tempting to wonder why exactly the Yankees couldn't use Joba Chamberlain this way while breaking him into the majors this year.)

Gossage was an exceptionally durable reliever, but there's more to the story than just his innings totals. He pitched more than 130 relief innings three times, something that was done 28 times during his career and has not been done since. He pitched more than 100 innings four times, but that was done 221 times during the span of his career, and has been done just 16 times since. And especially in the Bronx, after the years in which he was used most heavily, Gossage was somewhat injury prone: From 1978 to 1981, at his physical prime, he missed two different half-seasons to injury.

None of this affects his qualifications for Cooperstown at all — he should have been in years ago, and his decade of true dominance makes him vastly more deserving than most of the more than 50 men and women who have been enshrined in the Hall since he was first listed on a ballot in 2000. But just as ballplayers can personify their times in some ways, so can they personify ideas. And the idea that Gossage would like to personify is that relievers were tougher in his day, and that baseball was better. He'll tell you: Last year he was quoted as saying dismissively, "Don't even compare what Mariano does to what we used to do."

So far as Gossage's line of argument is meant to make himself look good, there's nothing wrong with it. The man is certainly entitled to a bit of self-promotional bluster. The problem comes when people try to apply that reasoning to today's game as a hammer against today's players.

Mariano Rivera and Trevor Hoffman may not be as tough as Gossage was, and they may not be used as efficiently, but both are still dominant at an age when Gossage had long since lost his effectiveness. Moreover, Gossage was very much affected by the times in which he pitched. Yes, he was able to pitch 130 innings a year; but there was always someone around who was used that way. It wasn't a really rare or singular thing to do, but rather something pitchers did when the game was played differently. DJs don't run their systems out of lamp posts anymore, managers don't punch star players on live TV, and Joba Chamberlain isn't going to throw 130 innings in relief this year. In all cases, that's probably a good thing.

tmarchman@nysun.com

No comments:

Post a Comment